Last year I took a critical look at a dynasty squad that I’d been neglecting for a bit and decided it needed a genuine rebuild. And I decided I wanted to “liveblog” the process because I’ve been playing dynasty since 2007 and I’d never done a genuine rebuild before.

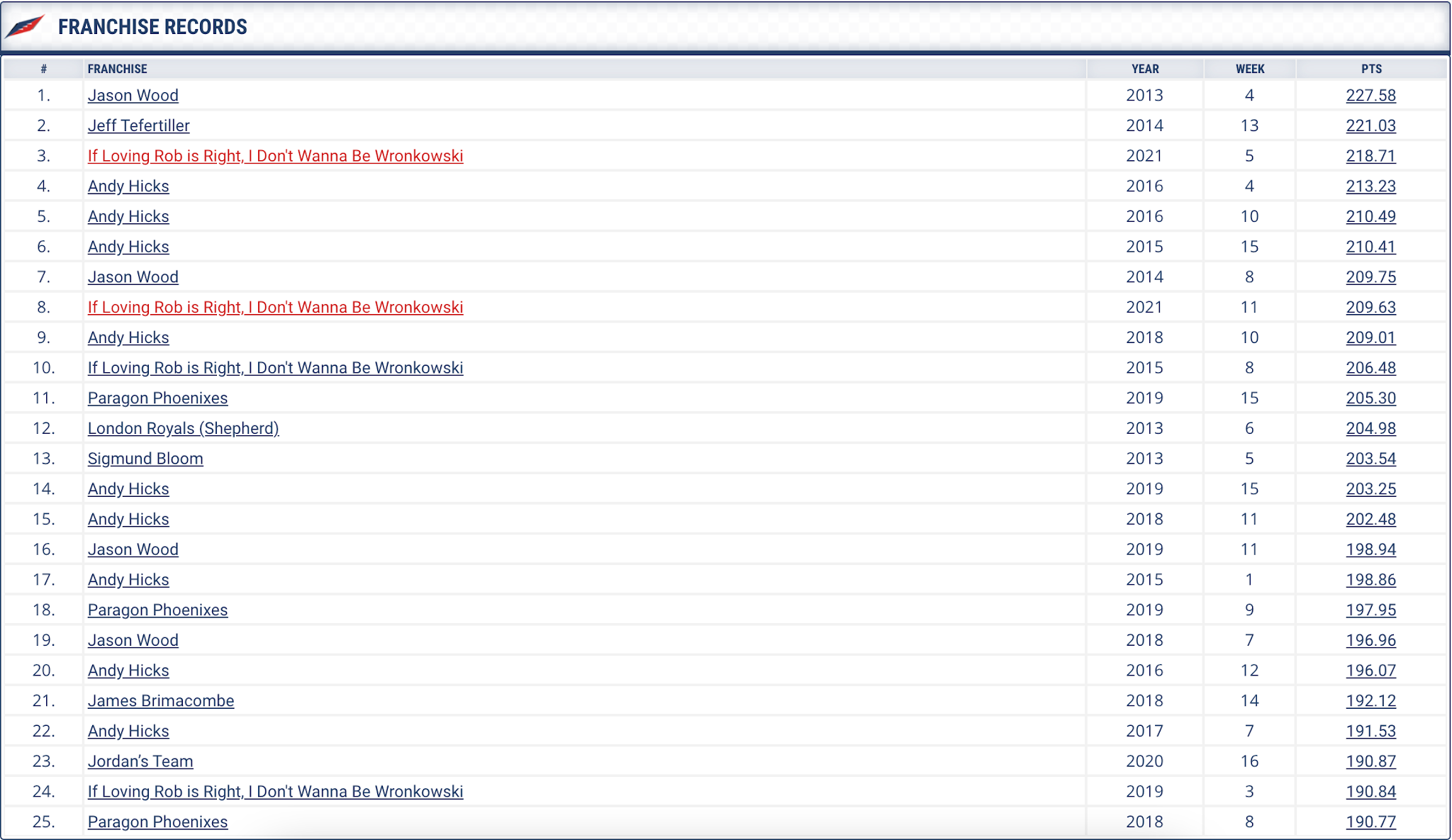

This partly is a not-so-humblebrag. I’m good at dynasty. I only have two dynasty teams, but in the oldest, I’ve finished 3rd, 3rd, 8th, 7th, 3rd, 1st, 1st, 4th, 1st, 1st, 1st, 2nd, 2nd, and 2nd in scoring (out of 10 teams).

I maybe *SHOULD* have gone for a full rebuild in 2009-2010, but at the time I was inexperienced and didn’t know enough to pull the trigger, so I muddled through as I’d been doing and managed to get enough value from buying injured players to climb to the top. Since then, my primary job on that team has been refreshing, constantly turning over my roster to try to stave off the headwinds of parity.

This is also partly a criticism of myself. In my other league, I decided to try “productive struggle” during the 2013 startup (loading up on young players and injured stars with the goal of nabbing a high rookie pick and coming out strong in Year 2). I finished 12th in Year 1, then 9th, 2nd, 4th, and 4th in years 2-5, taking home a title at the end of 2017. All-in-all a strong vision and successful execution.

Then I started neglecting the team.

I’m normally a very high-volume trader, but after 2015 I was distracted and wasn’t putting in the effort to refresh my roster. In 2018 my point total fell to 8th. In 2019 it fell to 10th. Thanks to some fortunate schedule luck I made the playoffs both seasons and deluded myself into thinking I was contending.

If I were investing in the team the way I should have been and I were more clear-eyed about my prospects, I would have begun the rebuild years earlier. Instead, I papered over the decline and let the rot fester.

But I don’t have a time machine and I can’t make up for past mistakes. All I could do is start fixing things going forward. And as I said, I wanted to document the process, partly as a roadmap for anyone else facing a similar decision, and partly as a time capsule so that afterward I could reflect on my thoughts and my processes and improve my game going forward.

A Recap of the Action So Far

Part 1: an in-depth discussion of the state of my team, how I let it get that way, why I decided to rebuild, what my plan was for the rebuild, and the first steps I took along the way.

Part 2: reaffirming the vision for my rebuild and detailing the next steps, along with a treatise on how I trade. The philosophy and strategy behind why and how I trade along with a discussion on how can I be a high-volume trader in leagues that are often derided as “inactive”. Also, a representative and complete set of trade negotiations from start to finish.

Part 2.5: Written after the season, I reflect on some of the thornier strategic questions I faced, detail the final roster-shaping trades I made before the deadline, and evaluate all of my moves both with and without the benefit of hindsight.

Part 3: Offseason negotiations and completed trades on through the rookie draft and some musings on where my team stood entering 2021.

Revisiting Some Thorny Philosophical Questions

Exiting the Rebuild

The two most important decisions of any rebuild are when to start and when to stop. Everything else is just details. I’ve written extensively about why I decided to start rebuilding, so I wanted to devote a bit of space to why I’ve decided to stop.

It is my strong belief that except in the most hopeless of cases, most rebuilds can be accomplished in the course of a single season. This doesn’t mean that they will be accomplished in a single season, only that they can. Successfully rebuilding requires a little bit of fortune (just like successfully doing anything in fantasy); if your plan for a rebuild hinged on trading for Cam Akers and J.K. Dobbins and drafting Travis Etienne, and your wide receiver corps included Michael Thomas, Michael Gallup, Jerry Jeudy, and D.J. Chark, and George Kittle or Logan Thomas was your top tight end, well then… sorry, that rebuild is going to take another year.

But when planning a rebuild, you need to leave an off-ramp. You need to have some process in place that lets you switch to contending mode as soon as your roster is up for it. This doesn’t mean a willingness to make a bunch of win-now trades; I

hate win-now trades and think they should often be termed “lose-later” trades instead.

But it does mean being able to quickly pivot back to considering current value and yes, possibly even making trades that shift future production into the current season provided the total net value is still in your favor. (My complaint against “win-now” trades is not that they shift future production into the present, it’s that they sacrifice total value to do so.)

In June, I was ready to take that off-ramp. Jonathan Taylor and Cam Akers gave me a pair of Top 10 running backs, Kyler Murray, Justin Herbert, Mark Andrews, and Jonnu Smith left me strong and deep at both of the singlet positions, and my receivers looked like a mess, but they looked like the kind of mess that value could easily emerge from. Footballguys’ tools rated me as a Top 4-5 team, which meant I had a legitimate title shot.

Because I was ready to care about the present again, I traded Myles Gaskin and the 1.12 pick for Aaron Jones. Again, this isn’t a “win-now” trade because I felt like the value of what I was getting was greater than the value of what I was giving up. This means that if I misjudged and things didn’t go well, I could likely sell Jones later for more than I paid to acquire him. I was merely rebalancing my roster value.

Cam Akers’ torn Achilles put a serious crimp in my plans, taking away my roster’s biggest area of relative advantage (potentially starting three Top 10 RBs on a weekly basis). I was tempted to immediately reverse course, sell Jones again, and push my rebuilding off-ramp back to 2022.

I resisted this temptation and decided to let things play out for a bit. It was a good decision; my team is 5-1 and 2nd in points. If I’d given up before the season started I would have sacrificed a fantastic shot at a title. Again, knowing when to rebuild is important, but it’s just as important to know when to stop. And sometimes that means stopping early before you’re absolutely positive and seeing where the chips fall.

If things had broken differently and I was switching back to rebuild mode after Week 6, I probably would have lost some value relative to the counterfactual universe where I never gave this season a shot. I’d likely wind up with a later 2022 pick, I’d have risked injuries to some of my older players, and I’d have missed opportunities to sell players for future assets.

But the goal is ultimately to win championships, and giving the season a chance was worth more to me than any counterfactual losses.

Adding Short-term Producers

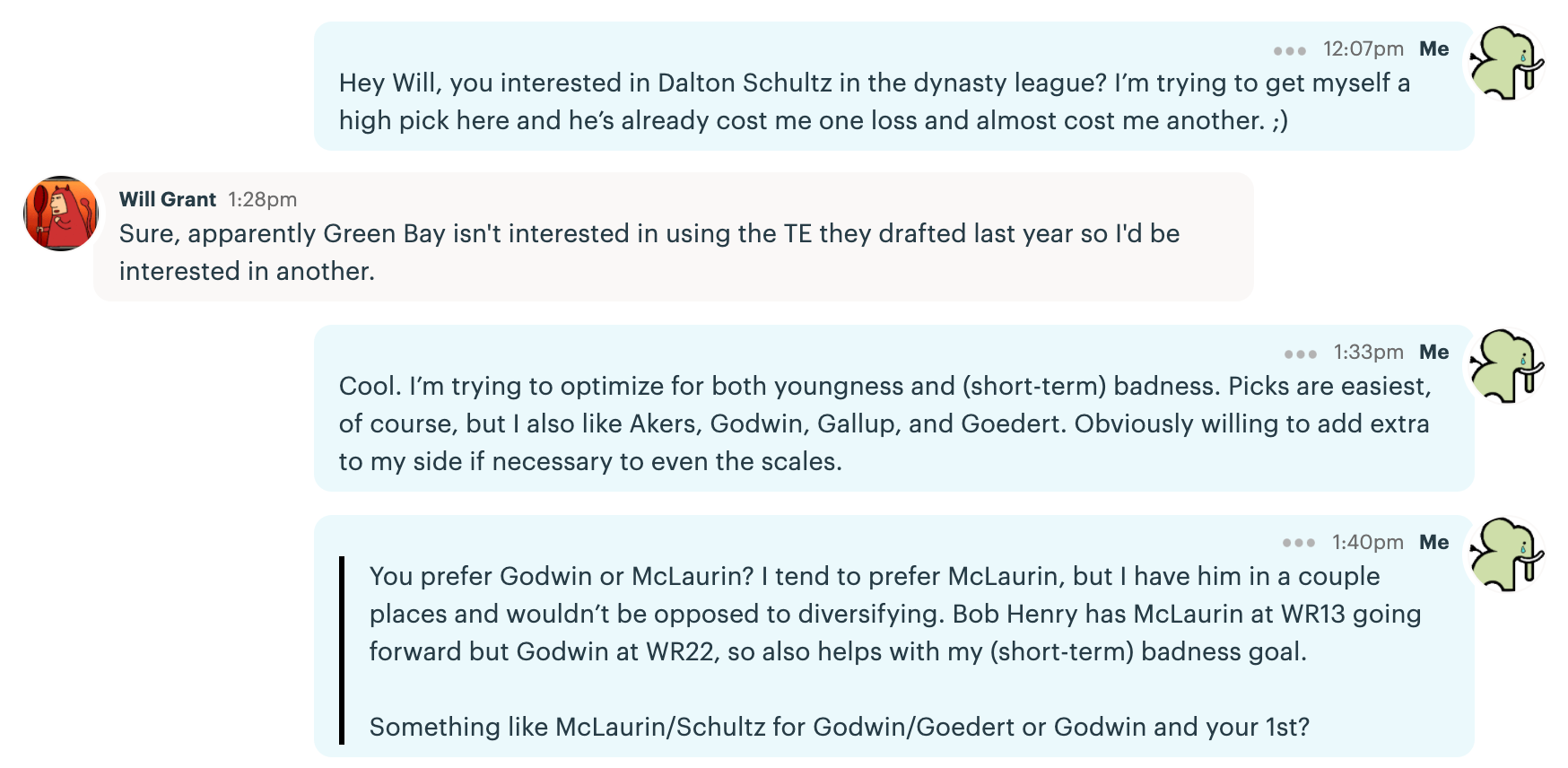

I’ve written this one to death. Last year I decided to spend big FAAB amounts to add Myles Gaskin, Dalton Schultz, and Drew Sample because all three players were young and productive. I did this despite knowing that there was a good chance all three would cost me draft position only to see their value go to zero after the season.

The gamble paid off overall. They did cost me a bit of draft position, but based on future trades, I netted the equivalent of two late 1sts for Schultz and Gaskin. Ironically, the one who seemed most likely to see his value go to zero (Schultz) is the one who has done the best, which should be a reminder of the huge amount of uncertainty inherent in this hobby and the reason why I’ll always make a positive gamble like this.

Also, somewhat related, I felt that despite being older than I’d like, Leonard Fournette offered asymmetric upside. He had a better chance of seeing a big value spike than similarly-priced players, so I held on to him rather than getting younger. That was a good decision because his value, it’s a-spiking.

(I also held on to Chris Herndon for a similar reason. The nice thing about bets like these is that even if you’re wrong, you just cut the player and grab someone else. You don’t have to hit every one to turn a nice profit.)

Studs vs. Depth

This question isn’t actually related to the rebuild. Historically,

my preference in dynasty is to build a top-heavy roster. I’d rather have a receiving corps that was three Top-20 WRs and a bunch of guys ranked 60+ than a receiving corps that had no stars but 6 or 7 guys in the 20-40 range.

But I’d been seeing that preference become a crutch. While they had once been one of the most effective tools for adding value to my roster, I’d been self-scouting and noticed that I was bleeding value on 2-for-1s. Not a ton, but some.

The error I was making was generally not respecting the uncertainty that I mentioned above with Dalton Schultz. A lot of guys who are in the 20-40 range today will break out and quickly ascend the rankings. The problem, for our purposes, is that we don’t know which ones in advance, so a bet on a guy in that range is individually risky.

But if you aggregate enough individually risky bets, the end result is a relatively safe bet. Since I was already experimenting with my roster, I wanted to try harnessing this and loading up on a deep, young corps of major question marks. I figured some of them would hit big and some of them would bust, but overall I was very likely to get usable production from somewhere. And since everyone was young, even the guys who didn’t become productive should still hold value. In theory.

After the draft I had a WR corps of Ja’Marr Chase, Tee Higgins, Marquise Brown, Jaylen Waddle, Laviska Shenault, Elijah Moore, Henry Ruggs, Devin Duvernay, and Quintez Cephus. That’s nine receivers, all pre-breakout, all 23 or younger (except for Brown, who was 24), all entering their 1st or 2nd season (except Brown, entering his 3rd), most with massive draft capital (drafted 5th, 6th, 12th, 25th, 33rd, 34th, 42nd, 92nd, and 166th in their respective classes).

None of those guys was expected to be much of a contributor this year. But their profiles suggested a reasonable chance that they each would be, and overall it seemed a virtual certainty that some of them would hit.

Through six weeks, Ja’Marr Chase and Marquise Brown have been the #6 and #7 fantasy receivers. Jaylen Waddle (27th) and Henry Ruggs (33rd) have both overperformed expectations to serve as capable WR3s or flex plays. Tee Higgins had the highest expectations of anyone on my roster, and he has missed time and underperformed a bit but also served as a capable WR3. Overall, I’m 8th in WR scoring despite being slow to trust Marquise Brown and flexing a wide receiver fewer times than any other team in the league (once in six weeks).

My receivers haven’t been great, but they’ve done their job; they avoided being a liability and they’ve done an absurdly good job at holding their value.

I’m not saying that I’m convinced this is the best path, either. But I’m certainly much more open to the experience of rolling with a deep-but-messy unit and trusting time to sort things out.

Diversification: good or bad?

I was faced with four specific situations last year where I had a player on both of my dynasty rosters and faced the choice of whether to diversify or not.

In the first, I opted to trade Terry McLaurin for Chris Godwin. I viewed this as a very small loss because I preferred McLaurin, but felt diversification was a compelling enough interest to justify it.

In the second, I opted to trade Brandon Aiyuk and keep Laviska Shenault despite slightly preferring Aiyuk to Shenault. Again, I felt diversification was a compelling enough interest to justify the small loss.

In the third, I wound up with Cam Akers in both of my leagues and tried to diversify, but felt the value was always just a hair short of what I wanted and repeatedly declined to do so.

In the fourth, I had Tee Higgins in one of my leagues and decided to acquire him in my other despite hurting my efforts to diversify simply because I felt the value was too big to ignore.

For starters, why do I care about diversification? Because it exposes me to less risk. If a player breaks out, I only benefit from him in one place. But if a player busts, I’m only hurt by him in one place, too. The more diversified my rosters are, the lower the variance, and low variance is a net positive provided you’re a +EV dynasty player.

(As an added bonus, diversification means you have more different players rostered, which is often more fun because you get to take part in more good things.)

So diversification is a compelling interest if value is equal. This doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a compelling interest if the value is not equal; I will be willing to take a small loss to diversify, but the devil is in the details. The question is “how small”.

If I had Patrick Mahomes in both of my leagues, I wouldn’t trade him for a 3rd just to be rid of him. That loss is much too large. I’d rather risk a potential loss in the case of a Mahomes injury or underperformance than lock in a guaranteed loss by selling him for so little.

In all four of the cases above, it looked like the choice I made was the wrong one. McLaurin genuinely looks like a better dynasty asset than Godwin. Aiyuk was substantially more valuable than Shenault for most of the last nine months.

Akers’ value took off like a rocket (he reached the first round in offseason dynasty startups), which made the decision against diversifying look great… until he tore his Achilles and devastated both of my rosters at once. And Higgins failed to take off like a rocket (as I expected when I acquired him), then took a value shock that I had to eat on both of my teams when the Bengals drafted Ja’Marr Chase.

Overall, I would have been better off putting in more effort to diversify *OR* putting in less effort to diversify as my half-measures gave me the worst of all worlds. But that’s outcome-centric thinking. I really should have pushed harder to move Akers and I really shouldn’t have put so many eggs into Tee Higgins’ basket, but diversifying McLaurin and Aiyuk was the correct call, even with hindsight. (We can see now the danger of judging things too quickly, too, as Shenault is poised to overtake Aiyuk in value once again.)

Prospect Is Its Own Position

This I think is perhaps the most important lesson for rebuilding. When you’re trying to contend you want a balanced roster. When you’re rebuilding, you just want to maximize value.

I think it’s best to think about your roster as a series of jobs. You have guys whose job is to increase the points you score at the quarterback position. You have guys whose job is to increase your points at running back, or at wide receiver, or at tight end.

And after all those jobs are filled you’ll still have roster spots leftover. The job of your 8th receiver is not to increase the points you score at wide receiver. The position that 8th receiver plays is not receiver at all, it’s “prospect”. Prospect is its own position, completely distinct from wide receiver.

You want different things out of a wide receiver than you do out of a prospect (even if that prospect happens to nominally be a receiver). For a receiver, the only thing that matters is his ability to increase your scoring at the position (in expectation, in a window that you actually care about). For a prospect, the only thing that matters is his ability to (at a minimum) retain value or (preferably) increase in value.

I’m going to repeat that because this is one of the most important points of dynasty. For a prospect, the only thing that matters is his ability to (at a minimum) retain value or (preferably) increase in value.

If you’re starting a player, then it’s okay if they’re losing value (as long as the value you gain from starting them outweighs the value they lose). If you’re not starting a player, the absolute only thing they cannot do is lose value. Adam Thielen is a fine WR3, but he’s a terrible WR5. Or to put it differently: he’s a great receiver but a terrible “prospect”. Prospect is its own position.

Generally this means you want your prospects to be young, but guys like Leonard Fournette show that age isn’t everything; even older players can have asymmetric chances of gaining value if they’re in uncertain roles that could resolve favorably. But the key thing is if a guy’s not starting you want him holding or gaining value.

If this means rostering 3 RBs and 9 WRs, that’s fine. In reality, you’re rostering maybe 3 RBs, 4 WRs, and 5 prospects. If the best prospects– if the players most likely to retain or gain value– are all receivers, then load up on receivers. If they’re all quarterbacks, then load up on quarterbacks. You’re just trying to field the best group of prospects you can. Prospect is its own position.

Eventually those prospects should help you put points in your lineup. Traditionally people imagine this happening by prospects “graduating” to receiver, improving enough that you’d consider starting him. This is why people don’t like overloading at one position.

But just as easily, prospects can be converted to points by trading them for someone who’ll log starts for you. If your prospects keep gaining value you will increase your purchasing power so you can buy more points when the time comes.

A prospect’s only job is to retain or gain value. Prospect is its own position.

Also, when you’re rebuilding, the only position on your roster is “prospect”. Every roster spot is a prospect and should be evaluated based solely on how it fulfills its job as a prospect.

Final Steps

Enough philosophy, time to sort out the final steps and recap where things stand today.

Near-Trade #11:

After I acquired Blake Jarwin (at the end of the last post), I immediately turned around and tried to trade him to the biggest Jarwin fan in the league. Said GM had Darrell Henderson, who I really liked in a vacuum but who was doubly valuable as a handcuff to Cam Akers. Leaving myself overexposed to Akers was a mistake, but one I could have hedged against with Henderson on my roster.

Unfortunately, I got greedy. Rather than offering Jarwin for Henderson straight up, I got him to agree that Jarwin was more valuable and tried to get a second piece. I offered Jarwin for Henderson and Gabriel Davis, but he balked.

I again had the opportunity to offer Jarwin for Henderson straight up, but loss aversion started messing with me. Given the TE-heavy nature of this league I started to convince myself that Jarwin was a solid bet to put up Top 12 TE stats, in which case his value would rise. Essentially I decided he had a great path to the role Dalton Schultz has claimed to this point.

I also neglected the fact that TEs are harder to trade, so even if Jarwin did hit Top 12 numbers I might not be able to get fair value for that.

I let things sit for a while as I tried to decide what to do, and while I was dithering, Akers tore his achilles and Henderson was off the table. I convinced myself that maybe this was for the best, that Jarwin really was a secret star, so when the Rams traded for Sony Michel and the buy window cracked back open I still couldn’t bring myself to make the offer.

I made some mistakes during the rebuild, but this (along with the failure to shop Akers more aggressively) was the only one that I genuinely beat myself up over. I genuinely knew the right thing to do and had a great chance to do it, but I got greedy, and then I got cold feet. Today Henderson is a Top 10 running back and Jarwin found himself among my most recent round of cuts.

The thing is he really did have that kind of upside. I just discounted the possibility that Schultz would be the one to fulfill it instead. And I behaved penny-wise but pound-foolish.

Actual Trade #11:

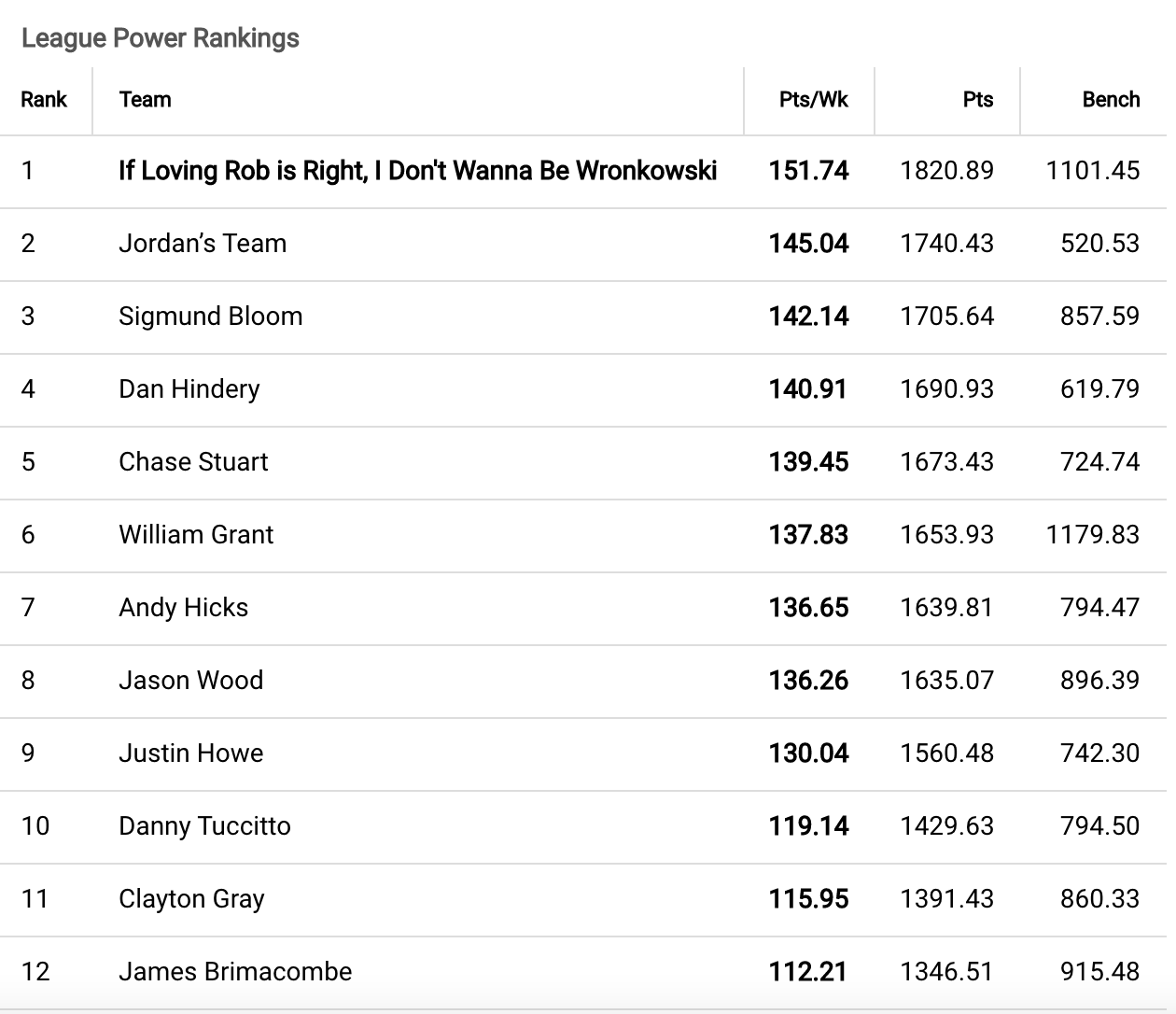

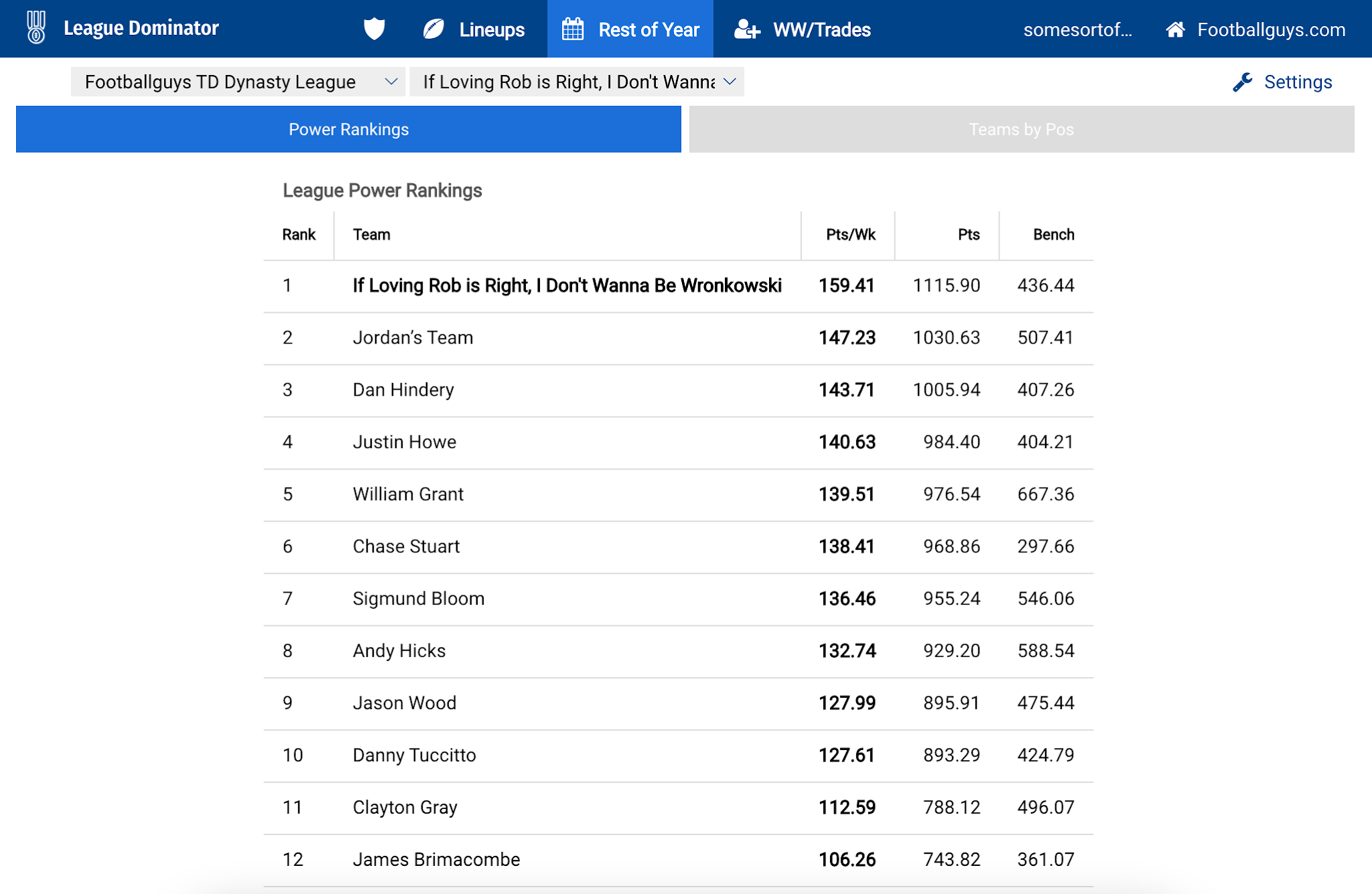

I opened the season 4-1, including a monster breakout game in Week 5 (the 3rd-highest-scoring game in league history and a bad start/sit decision away from #1). Footballguys’ league forecast saw my team rise from 5th to 2nd in the power rankings. I decided that I had a genuine opportunity at a title here and I wanted to take maximum advantage of it. Plus, I saw a market inefficiency to exploit.

I couldn’t pay up at fair market rates for Alvin Kamara or Dalvin Cook without seriously leveraging my future (as well as likely giving back some of the gains in the present). But Austin Ekeler profiled as a comparably-valuable dynasty asset for a fraction of the cost, and best of all, he was on a team that was 1-4 and Bottom 3 in scoring.

I gave the other GM his choice of either Jaylen Waddle plus my 2022 2nd, or else his choice of any two of Akers, Shenault, Ruggs, and my 2022 1st. He liked the second framework better and liked Akers and Shenault the best of the four options (I agreed), which put him around the top of budget for me. That wasn’t quite enough so he asked for my 2022 2nd, and I didn’t want to let something so small stand in the way (since I don’t much care for rookie picks after the top ~18-20, anyway), so I agreed.

Plus I managed to finally diversify Cam Akers. (Too little, too late.)

(Note, if you will, how this is a great example of me converting “prospects” into “starters”, too. Shenault was flirting with flex status for me so he wasn’t a “pure” prospect, but the other guys I could replace him with are just as productive, so he was pretty close. Mostly Shenault and Akers had one job– hold or gain value until I decided to cash them out for points.)

Trade #12:

The GM with Russell Wilson hasn’t even bothered carrying a second quarterback for the better part of the last decade, so when Wilson got hurt he was pushed to rely on the best available player on the street, in this case Ben Roethlisberger. I took advantage, offering either to trade Kyler Murray or Justin Herbert for a big package or trade Daniel Jones for a smaller one.

He offered his second for Daniel Jones and my 3rd. His second will likely be late, but so will my 3rd. In theory I like Jones more than that, but I got Jones for free off of waivers and I’d just traded away my own second, so there was some appeal to just banking the guaranteed profit.

One deciding factor was that trading Jones without getting a player back freed up a roster spot. (In this instance, I grabbed Jimmy Garoppolo– who I liked very nearly as much as Jones, anyway.) The other deciding factor is that the other GM would likely have Wilson back by the playoffs anyway, so this was unlikely to be a factor in the postseason.

My Roster, Post-Rebuild

For starters, again I’d like to reiterate that the rebuild was a smashing success. A year ago at this time I was 1-5 and projected 12th out of 12 teams in rest-of-year scoring. Today I’m 5-1, 2nd in total points, and projected to lead the league in scoring by a significant margin the rest of the way.

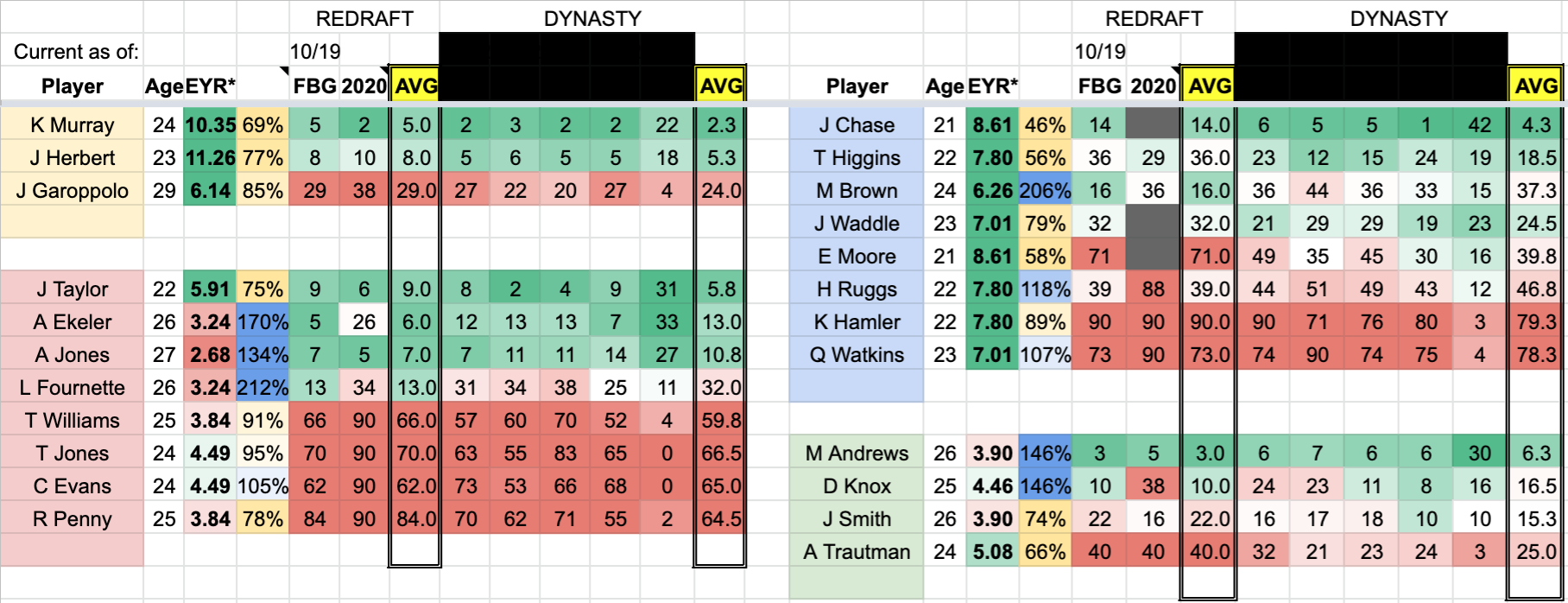

I accomplished this without mortgaging my future in the slightest. I estimate I have 14 players with significant value. 9 of the 14 have at least 5.5 Estimated Years Remaining (EYR) and 13 of the 14 have at least 3 EYR. (The exception, Aaron Jones, has 2.68 EYR.) Meaning my outlook shouldn’t be much different next year, and since I turn over most of my roster every two seasons, that’s all I need.

A good rebuild can easily be accomplished in a single season.

(Dan Hindery finished last year with the #3 draft position; he’s currently 6-0, 1st in points scored, and 4th in projected points going forward. Demonstrating again that a rebuild can be accomplished in a single season.)

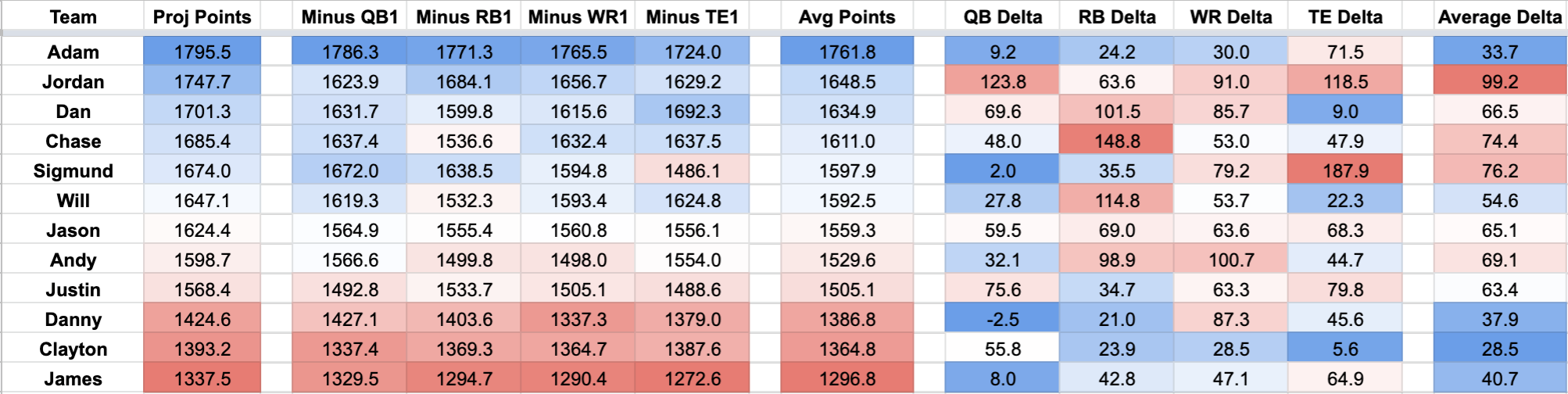

Moreover, not only is my team good, it is deep and robust. Here’s projected points scored by every team should they happen to lose their QB1, RB1, WR1, or TE1 to injury tomorrow. Because of my depth, tight end Mark Andrews is the only player whose injury or underperformance would meaningfully impact my bottom line. (Meanwhile, my top competitors are much more exposed to risk.)

Here’s my roster as it currently stands:

And here’s where each player was acquired:

At the beginning of this process, I mentioned roster stagnation as a sign of neglect. As a measure of this neglect, I mentioned that 29% of my roster had been acquired through trade, while only 66% of my roster had been acquired in the last two calendar years.

Today, 11 out of 23 non-defense players were acquired via trade (49%), while a whopping 23 out of 23 (100%) have been acquired in the last 730 days, 22 out of 23 (96%) have been acquired since the beginning of 2020, and 20 out of 23 (87%) have joined my roster since I began the rebuild just over a year ago.

Most importantly, I’ve managed to reach contender status without sacrificing my competitive future. There’s been a lot of good luck involved in the process, both in terms of the trades I made and in terms of the trades I avoided (good thing the Clyde Edwards-Helaire GM declined my offer of Alvin Kamara for him straight up!)

But at every point of the process I’ve stayed young enough and flexible enough that if things didn’t break right I wouldn’t have to start back over from square one.

Final Roster Evaluation

This series has already been extremely long and rambling. That’s what happens when I write without a specific goal and without an editor. But since this is as much (or more!) for my sake as it is for yours, I’m just going to keep writing. It’s important for me to be able to revisit my old processes and determine when they need to be updated, so having a contemporaneous record like this is immensely useful.

To that end, I want to walk position-by-position through my roster and discuss how I view the players as best serving my overall vision for the team. I will discuss each player through one (or more) of four prisms: cornerstone (young, super-talented player who I expect to anchor my squad for a long time to come), mid-term starter (talented and productive player who will give me a positional advantage or reasonable trade chip for the next 2-3 years), short-term starter (player whose primary purpose is to put additional points in my lineup over the next year or two and for whom any value beyond that is ancillary), and prospect (player whose only job is to retain or gain value).

Quarterbacks

Kyler Murray / Justin Herbert

I’m evaluating these two together because it’s hard to tease them apart. Either one of them is more than capable of serving as a CORNERSTONE for my team. Both are unbelievably young and talented with the potential for 10+ years as a starter. Both provide a short-term positional advantage and yet also rank higher in dynasty than in redraft.

Ordinarily it would be bad process to invest so much capital rostering two high-end players at a singlet position, but because they are so young and both rank higher in dynasty than in redraft, whoever doesn’t serve as my starter is more than capable of serving as a PROSPECT. Meaning whichever one is on my bench is still a good bet to retain or gain value. There’s no compelling reason to trade one of these quarterbacks for help today when I can trade either for just as much help a year from now.

(And if I’m wrong about one of these quarterbacks being a cornerstone, having the second gives me a necessary redundancy at the position.)

Running Backs

Jonathan Taylor

There are currently 12 running backs in the Top 12 rest-of-season rankings. (I know, right?!) Of those 12, only three are younger than 25 years old: Najee Harris (23), DeAndre Swift (22), and Taylor (22). Harris, Swift, and Taylor all have 5+ Estimated Years Remaining (EYR) by my historical formula and everyone else is under 4. That makes Taylor a CORNERSTONE at the position where cornerstones are hardest to come by.

I think a credible argument could be made at the moment for ranking Taylor as the #1 asset in dynasty. I don’t know that he is, but I certainly think he should be in the conversation.

Austin Ekeler / Aaron Jones / Leonard Fournette

Of the remaining Top 12 running backs, two are 25 (McCaffrey and Mixon), five more are 26 (Kamara, Cook, Ekeler, Elliott, and Fournette, who has jumped up to 12th since I started writing this post), and two more are 27 (Henry and Aaron Jones, who is currently 26 but I count this as his age-27 season because he’ll celebrate his birthday before the end of the season). All of these guys are fantastic MID-TERM STARTERS, providing a significant advantage with ~3 EYR left.

This is slightly inefficient for me because I can only start three of my four Top 12 backs a week, and that requires locking my flex in at the position. I would be open to trading away one of Ekeler, Jones, or Fournette for good value. But I’m also fine standing pat, because between the bye weeks and injury rates at the position, all four of my backs have a good chance to see my starting lineup plenty of times. And none are so old that I’d expect their value to crater over the next 365 days absent injury or severe underperformance.

Wide Receivers

Ja’Marr Chase

Six games in and he’s already a CORNERSTONE. During the draft process he was hailed by many as the best prospect since Calvin Johnson. Through the early going he’s been the best rookie receiver since Randy Moss.

Tee Higgins / Marquise Brown / Jaylen Waddle

All are phenomenal PROSPECTS who double as MID-TERM STARTERS given my lack of established veterans at the position. Young wide receivers are my favorite prospects because they tend to have the least downside risk of anything except for future rookie picks. If one of these guys blows up he has the potential to become a cornerstone, though I’m not counting on it.

Tight Ends

Mark Andrews

Andrews is right on the edge between CORNERSTONE and MID-TERM STARTER. He’s a touch older than I’d like, but the position as a whole skews old (thanks to the famously tough learning curve) and it seems to be aging better than historical trends would have predicted (though that might be noise). Regardless, he’s a massive weekly advantage in this wacky TE-crazy scoring system.

Dawson Knox

Three weeks ago a pure PROSPECT, Knox has ascended to the rest-of-year Top 10 which makes him a MID-TERM STARTER, too. A potential flex through the bye weeks and a nice backup plan should disaster befall Andrews.

Defenses

Los Angeles Rams / Carolina Panthers

Defenses are never cornerstones or mid-term starters, the best they can be in anticipation are SHORT-TERM STARTERS. When rebuilding you’re required to carry one, but you’ll want to treat it as a prospect. Last year I carried the Rams all season. The point wasn’t to maximize my weekly production, it was to say “I want to bet that the defensive unit with Aaron Donald will be relevant when my rebuild is over”. This year I’ve added the Panthers and am carrying two (at the expense of an extra prospect) because both profile as Top 10 units and their matchups line up well.

Prospects. (Prospect is its own position.)

Jimmy Garoppolo

The perfect example of how a player doesn’t have to be young to be a PROSPECT. Garoppolo is available on the cheap (I just acquired him off the street for free) but will likely be returning to the starting lineup. Maybe he plays well and parlays that into a long-term job somewhere, in which case his value will rise. We’ve seen him perform as a viable fantasy starter before, and his offensive system is enviable. We’ve seen veterans keep exciting rookies glued to the bench.

Maybe he doesn’t, in which case his value… can’t really fall since it’s zero to begin with. He’s much more likely to see a value bump over the next six weeks than, say, Kyle Trask (who is typically more what someone would think about as a prospect at the position). One of the most valuable traits a prospect can have is short-term uncertainty, because you’ll find out very quickly whether the value is going to spike or not and cash it in if it does or move on if it doesn’t. The worst kinds of prospects are the ones you’ll need to commit to for years before seeing any returns.

Ty’Son Williams / Tony Jones / Chris Evans / Rashaad Penny

All of my potential starting slots are well accounted for, so the remainder of my backs are not really running backs, they are PROSPECTS, and my only concern is how likely they are to retain or gain value. All four backs are 24 or 25, which is a little older than I’d like, but not too troubling. All have performed well enough to climb a depth chart and potentially position themselves an injury away from relevance. Their value when I acquired them was zero so there’s little downside risk, they’re mostly just lottery tickets that I’m holding and hoping for a spike. For that purpose, they’re… fine.

Elijah Moore / Henry Ruggs / K.J. Hamler / Quez Watkins

Pure PROSPECTS, although Ruggs has been playing well and could find his way into my flex or WR3 spot from time to time. Moore and Ruggs have draft position and youth on their sides. Hamler was also highly-drafted and hasn’t really had a great chance to fail; I like him as a cheap flyer at the position. Quez Watkins doesn’t have the draft capital, but he’s managed to surpass first round pick Jalen Reagor on the depth chart and is averaging 50 yards per game as a sophomore 6th round pick. His arrow is pointing up.

Jonnu Smith / Adam Trautman

I really thought Smith was going to be a mid-term starter for me, but his arrow is trending down. I wish I’d sold him a couple months ago, but hindsight is 50/50. As of now, I’m just holding and hoping for a value spike again (an injury to Hunter Henry, more involvement in the gameplan, something.)

Trautman was the most recent addition to my roster as I cut Blake Jarwin for him. This is a great example of prospect being its own position; Jarwin will probably outscore Trautman, but Trautman is more likely to see a value spike, and if he does, it’s likely to be significantly larger. I like grabbing former favorite TEs when impatient teams give up on them early and hoping for a post-hype breakout. Trautman reminds me a lot of Dawson Knox, who was drafted 9 picks higher one year earlier.

Week 11 Update

Just a quick check-in to see how that rebuild is going…

Yeah, pretty good.

Start-of-Playoff Update

#1 seed, 157.3 points per game average (league average: 127.0; 2nd-place: 142.4). Among non-QBs, I have the #2, #3, #4, #10, #15, #26, #33, #39, and #41 overall scorers (plus the #3 and #10 QBs).

The End

The goal was to write up a rebuild from beginning to end, and now I’ve done that. Maybe I’ll update after the season with how things went, but overall I consider this series concluded. I hope you’ve found it useful and applicable to your own leagues. I hope when I reflect back in the future that I find it useful as well.