This post continues my running commentary on how (and why) I’m rebuilding one of my dynasty teams. The goal is to give you all a glimpse into my process so you can see how I play dynasty and take from it whatever lessons you want. (I’m even happy to serve as a cautionary tale if you want!)

The first part walks through the decision to rebuild and all the moves to date. It covers a lot of my philosophy on how I value players and how I try to construct my rosters. I wanted to split this update into a separate post partly to preserve readability, but also because I plan for it to be a super deep dive into the philosophy behind how I trade and, as such, it should have standalone value even to people who don’t care about the larger rebuild.

Week 5 Update

Dalton Schultz is quickly becoming a problem.

Schultz was a high-cost waiver add after Jarwin’s injury in Week 2. In Week 3, Schultz put up 13.2 points in a game I won by 0.43; my second choice at the flex scored just 4.2. In Week 4, Schultz put up 22.8 points in a game I lost by 1.13; my second-choice flex scored 13.6. Worse, these two close games came against two of my top competitors for the 1.01 pick, with the team I beat arguably being the top competitor. These wins and near-wins could prove costly in the long-term.

At the same time, because of this league’s insanely TE-friendly scoring (1.5 points per reception *AND* 1.5 points for every 10 yards, which works out to something roughly equivalent to 2.2 points per reception for most tight ends), Dalton is potentially a very valuable asset.

Bob Henry projects Schultz as the #8 tight end going forward. He’s 24 years old and was drafted with the 137th pick of the 2018 draft, a range that is often fertile for productive tight ends. (Julius Thomas was drafted 8 picks earlier, George Kittle was drafted 9 picks later.)

Knowing nothing about him except his age, draft status, and projected production, Schultz would probably be a Top 10 dynasty tight end right now. And in this scoring system, Top tight ends are roughly equivalent in value to wide receivers. (Schultz is projected to score roughly the same as CeeDee Lamb, Kenny Golladay, D.J. Chark, Justin Jefferson, or JuJu Smith-Schuster, just to put some names on it; imagine the advantage having one of those guys as your flex would provide.)

I also have Jonnu Smith, who is comparably young, comparably productive, and has a similar draft profile, and I don’t think an offer of a mid-2021 first round rookie pick would be enough to acquire him. So again, if we knew nothing else about Schultz, that would be what he was worth and I wouldn’t really care that he was potentially hurting my draft position. I don’t mind that Jonathan Taylor, Kyler Murray, Terry McLaurin, and Jonnu Smith are hurting my draft position, because they’re good and valuable long-term assets. I’d rather have them and the 1.04 than not have them and the 1.01.

But we do know something else about Dalton Schultz. We know that he got the job because Blake Jarwin was lost for the season, and that Blake Jarwin already has a long-term deal to remain in Dallas. (We also know that, as of now, Dak Prescott does not.) So it’s possible that this Top 10 production is only temporary. It’s possible that Schultz will materially worsen my draft position and then give me nothing to show for it in the long run. (Could I just bench him? Of course not. I will always field my most competitive team every week. It’s a matter of integrity.)

On the other hand… if Schultz finishes the season with 800 yards and 8 touchdowns, will Dallas really go away from him? Or will he cement a long-term role? This is the dilemma; Schultz is Schroedinger’s Tight End, simultaneously both a Top-10 player and not a Top-10 player until observation next season collapses him to one path or the other.

For me, I see just one way out of this dilemma posed by Dalton Schultz: trading him to someone who actually *wants* his points this year. That way they can benefit from him in the short term, and bank the possibility of long-term value after that as a bonus. Meanwhile, I get an immediate return on my investment (hopefully return enough to offset the one win I already accidentally stumbled into).

So that’s priority #1 in Week 5. Dalton Schultz must go. For fair value. Because being motivated to sell doesn’t mean you should settle for less than fair value, it just means you should be willing to work harder to try to get it.

I want to take this opportunity to do a deep-dive into my trade process. Several of my leaguemates have told me that they feel like this isn’t a very active league, and yet with my Schultz deal I have completed five different trades with four different owners over the course of the last three weeks. I have sent away 16 players and two draft picks, and I have received 15 players and four draft picks. These stats belie the claim that the league is not very active. I wanted to look at why that might seem to be the case for others but not for me. So here’s a quick rundown of my entire philosophy and approach to trading.

Step #1: Identify Potential Trade Partners

Every good trader is good in his or her own way; bad traders are all alike. And the thing they all have in common is they never even bother to consider how a trade offer looks from the perspective of the other team. Looking at things from the other team’s perspective should always be the very first step of the trading process.

There are three main reasons people make trades. They can use trades to replace players they like less with players they like more. They can use trades to distribute value from a position of strength to a position of need. They can use trades to move future value into the present (or present value into the future) to shift their competitive window. (Great trades can accomplish two or even all three of these goals at once.) But if they’re not accomplishing something that they feel benefits their team, why on earth would they ever agree to a deal?

My goal is to move value from the present into the future. As a result, I don’t care about the present value of any assets I might receive in return. So I rule out any teams in the league that don’t have future assets commensurate in value to what I’m trying to sell. Everyone is really, really good at doing this part of evaluating trades, at looking at potential deals and deciding whether they get anything out of it.

But how many do the opposite? How many take even a moment to think about how the other team benefits from a deal? Good traders always do this. Bad traders never do this, they just indiscriminately send out offers that benefit their own team and then act puzzled when they all get rejected because they make no sense for the other team.

So my trade partner here must be willing to move future value into the present. Which eliminates any team that’s in a full or partial rebuild, because for them Schultz presents the same dilemma he presents for me. (I like to use Footballguys’ League Dominator, which has a “

projected team strength” tab that makes it easy to separate the potential contenders from the potential rebuilders.) This eliminates five teams for me. I’m just not going to bother pestering them about a deal here, because it will waste their time as well as mine.

Additionally, I’m not looking to move “present value” in the abstract, I’m looking to move Dalton Schultz, a Top-10 redraft tight end. I’m not going to bother talking to the GM who already has Zach Ertz and T.J. Hockenson. Why the hell would he want Schultz, too? Why should I waste his time running down a deal that he gets nothing out of?

This leaves me with five potential GMs for whom I potentially have something they want, and who potentially have something I want in return. I rule out one because in previous trade discussions I have discovered he’s not interested in selling the things that I’m interested in buying. (Sometimes I’ll send a half-hearted “you interested in this guy?” just because it’s low-cost and on extremely rare occasions can lead to productive deals. But in this case I’m pretty confident in my assessment, so I pass.)

This leaves me with four targets. Another one I’m skeptical of, because we’ve already made two trades and at this point he’s running out of players who fit my needs. (The best I can think of would be Dalton Schultz for N’Keal Harry, which… is way less than I’m hoping to get here.) So I put him on the backburner as a last resort and focus in on the other three.

Step #2: Establish my Values

If I want to trade someone, I need to know two basic things: what I think is fair value for him, and what’s the minimum I would take for him.

These values need to be very broad so they can apply to all potential trade partners. I generally like to express them in terms of future rookie picks, because future rookie picks are a universal currency. But especially in a case like this where my preferred return genuinely would be future rookie picks, it’s a useful framing.

In a vacuum, I think fair value for Schultz would be a late 1st (or equivalent value). If one were to draft a tight end in that range, it’s 50/50 whether they’ll ever be projected to give a season as valuable as the one Schultz is giving now, and (given the learning curve at the position) even if they do, it’ll be years down the road and therefore intrinsically less valuable.

In practice, getting Schultz off of my roster has some value to me because it improves my 2021 picks in expectation. So I can take a bit less than fair value and still feel like it was a net gain for my team. This means I’d be willing to settle for a high 2nd (or equivalent value).

Establishing values means nothing if you aren’t prepared to walk away if they aren’t met. This is perhaps the most important part of trading. If you’re not willing to walk away from lesser offers, then you haven’t established good values. But you need to figure this out in advance because once negotiations start, emotion starts to get the better of you.

No one will ever go broke walking away from bad deals. A willingness to walk away often causes trade partners to reconsider. But even if not, you can always shop again in the future (perhaps after injuries to other tight ends), or even hold and hope that the long-term value hits. It’s a risk and one that I’d rather not take, but one I’m willing to shoulder if the potential return isn’t worthwhile.

Step #3: Establish a Dialogue

I’ve noticed that some dynasty GMs negotiate primarily through formal offers and counteroffers. They’ll send me a low-ball offer for one of my players with the expectation that I’ll not simply reject, but offer a counter. From there we send forth a deal of counters and counter-counters, trying to guess at what the other owner really wants until they blindly stumble onto an acceptable deal.

This system works great in some leagues and with some GMs. And it works absolutely terribly in other leagues and with other GMs.

I don’t do that. After I’ve narrowed my pool of trade partners and figured out a rough outline of what I’m looking to give and what I’m hoping to get, I… talk to the other GMs. Like, using my words. Usually when I’m trading I’ll only ever send one offer on our league host, an offer that has already been agreed to in principle and which is immediately accepted. (There are exceptions: I’m comfortable playing the Offer-Counter game with GMs who prefer to negotiate that way, though I’ll usually try to maintain a parallel dialogue while we play it.)

This system is a lot more work than just firing off potential deals. A *lot* more work. Most of the time I’ll send 50 messages back and forth with someone only to discover that there’s no deal to be had. But even failed negotiations serve a purpose. They give me an opportunity to demonstrate that I’m a good-faith negotiator who is looking to make mutually beneficial deals. They lay the groundwork for future trades. (The key here is actually, you know, being a good-faith negotiator who is looking to make mutually beneficial deals.)

While it’s more work, the results I find are terrific. Again, I’ve heard several times that this isn’t a very active league. And yet of the 23 players that were on my active roster three weeks ago, just 8 remain today. (Justin Herbert, Leonard Fournette, Boston Scott, Darrynton Evans, Henry Ruggs, John Ross, O.J. Howard, and Chris Herndon.) I’ve picked up three extra first round picks during that span. I can’t say that my way is the best, but I can definitely say that my way works.

So, with three GMs identified, I send quick introductory messages to each.

- “Hey my man, you interested in Dalton Schultz? I’m out here trying to get a high rookie pick and he’s already cost me one loss and almost cost me another. This kind of production can’t be tolerated.”

- “Hey, interested in Off-Brand Jarwin?”

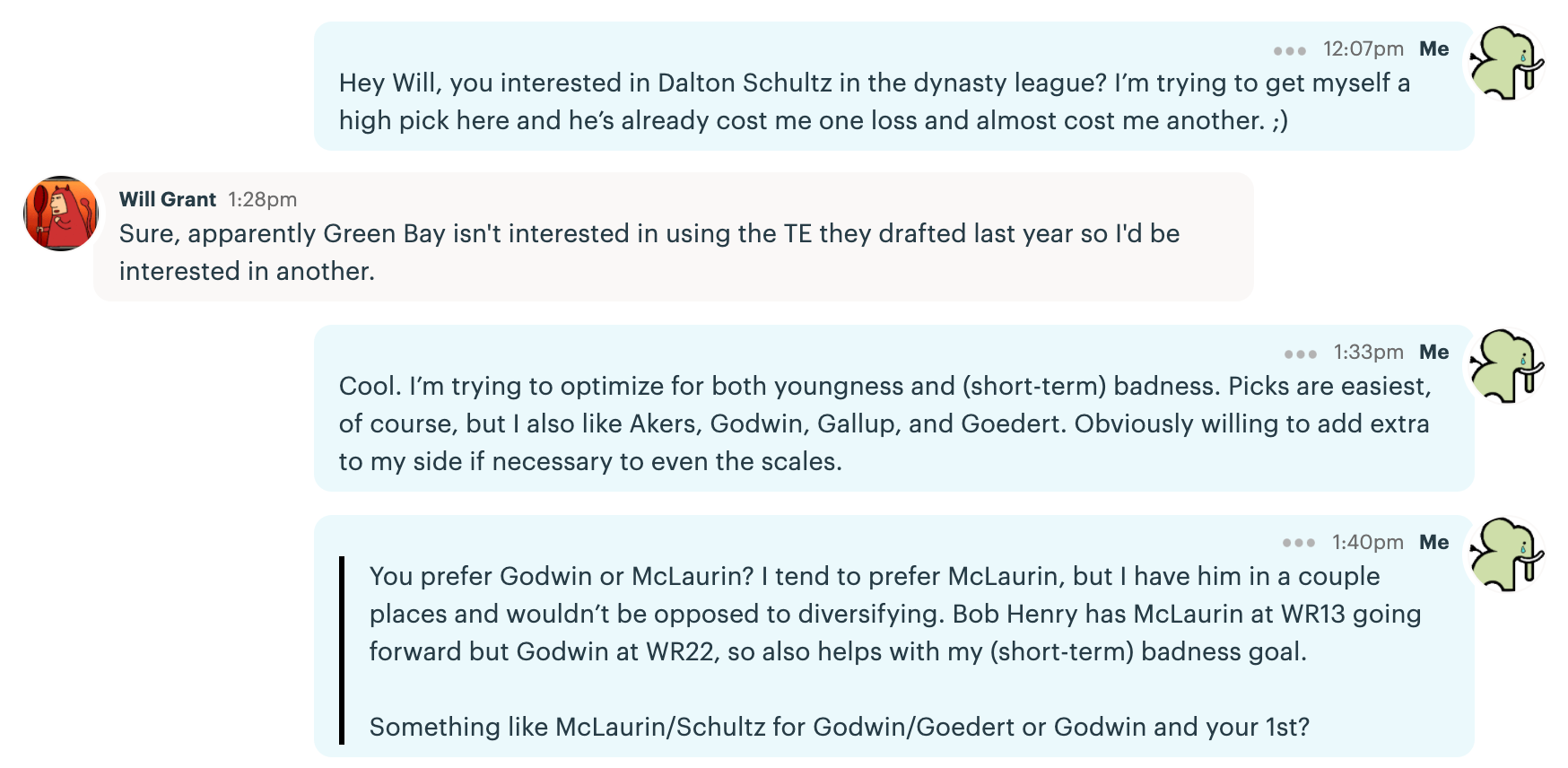

- “Hey Will, you interested in Dalton Schultz in the dynasty league? I’m trying to get myself a high pick here and he’s already cost me one loss and almost cost me another. ;)”

These messages are tailored to the chosen medium. (The first and third were sent over our office chat platform, the second shorter message was sent via Twitter DMs.) I use a light tone, but make it clear what I’m looking to do from the outset to make it easy for them to decide whether they’re interested before I pursue. I also tailor to my target audience where possible, such as referencing the fact that GM #2 was a massive Blake Jarwin fan before the season started.

GM #1 responds quickly. He mentions having drafted Schultz as a rookie, expresses reservations about his value in 2021 and beyond, and speculates that I’d want more than he’d be willing to give, but says he’s interested depending on the price.

I listen to what he’s saying. He’s open, but only if he can get a market discount. I take note and quickly shoot off a quick line mentioning the lowest range of what I’d be willing to settle for so he can consider it (I say I’d be looking for Chase Claypool or a high 2nd– gently hinting that I’d want my own, which I had traded to him in an earlier deal, and not his, which I believe will be on the later end of of the spectrum.)

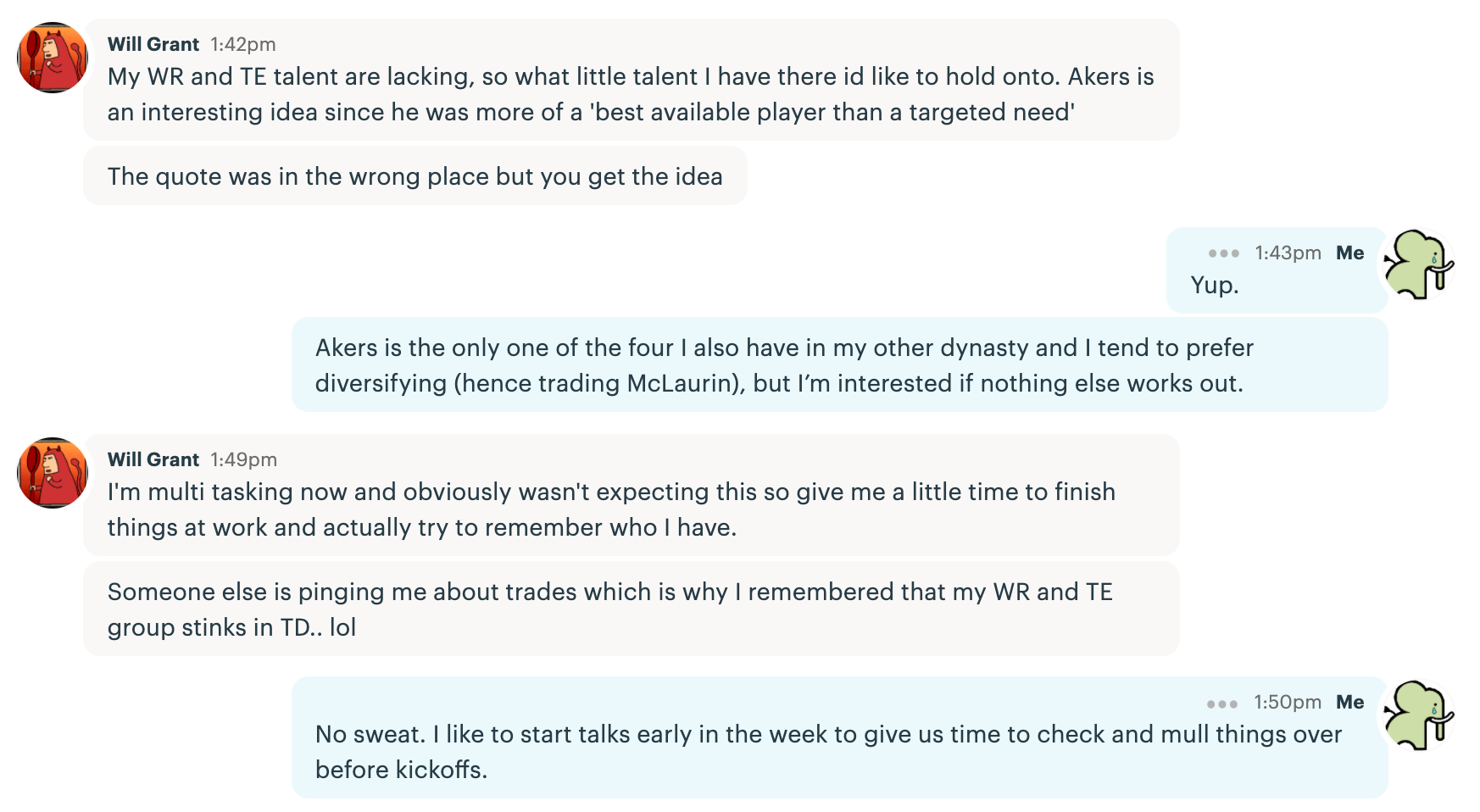

Then move on to the other GMs. I figure this GM could potentially serve as a fallback if I can’t get what I consider fair value somewhere else, but my efforts won’t see a huge return, so I direct them elsewhere.

GM #2 isn’t very interested, either. As I alluded to, he is a Blake Jarwin fan, which means he’s extra inclined toward skepticism regarding Schultz’s long-term outlook. I shoot for Schultz plus a little extra (Teddy Bridgewater, taking note of the other team’s lack of depth at quarterback– he has Russell Wilson as his starter, but his backup is currently Nick Foles) for Tee Higgins or Diontae Johnson (who I value at that “late 1st” level of return that I’m shooting for).

The GM responds mentioning Christian Kirk, who falls below my minimum return. I make a quick joke about his willingness to run without a backup quarterback (“I really like the “if Russ goes down we’re fucked and we don’t practice fucked” energy, btw.”) and mention perhaps doing Schultz + Quintez Cephus for Johnson or Higgins. He says the price is too high, but he’d potentially re-evaluate if Travis Kelce (his starting tight end) ever gets hurt.

This leaves GM#3 as my last best hope. Fortunately, GM#3 is interested. And he’s also agreed to let me publish our trade discussions so y’all can see the blow-by-blow of just how I think a good win/win dynasty trade comes together.

A Few Key Thoughts

- First off, notice how I lead from the very top with how I value players. I’m never going to try to make it some kind of mystery how much I like a guy.

On the one hand, making your own player values opaque has some potential value. If you’re looking to extract the maximum possible value out of a trade, saying “I really like this guy” cedes some negotiating leverage.

But I’m never trying to be maximally extractive. I’m trying to find deals that work for both parties. Always trying to wring every single last drop out of every single deal is a good way to piss off other GMs and earn a reputation as someone people don’t like dealing with.

I want people to ENJOY trading with me. I want it to be fun for them. And I want to get positive value while I’m at it. Not necessarily MAXIMUM value, but positive value. I’m not going to make any deal that doesn’t help me, but I’m also not going to play games and let a (purely theoretical) perfect deal get between me and a (reasonably achievable) good deal.

So if people ask me what I think about players, I’m going to tell them. If they ask me what my goals are in a deal, I’m going to tell them. I’ll tell them even if they don’t ask.

And more than that, I’ll tell them what I’m guessing their goals are and let them correct me if I’m wrong. I’ll say things like “It looks like you’re trying to make a run this year?” or “I’m guessing you feel like you could use some more tight end depth” or “I’m betting you’d like to get a bit younger”. And if they disagree, I listen to them. The question here isn’t how I would manage their team if it were my team, because it’s not my team. The question here is how THEY want to manage their team, and how I can help them accomplish that goal. And I don’t know how to answer that question if I don’t know what they want. And I don’t know an easier way to find out what they want than just… like… asking them.

- Second off, notice how flexible I am at the top.

I know how I value players. Until I’ve heard back from them, I don’t know how THEY value players. And I don’t want to foreclose on any possibilities by guessing wrong.

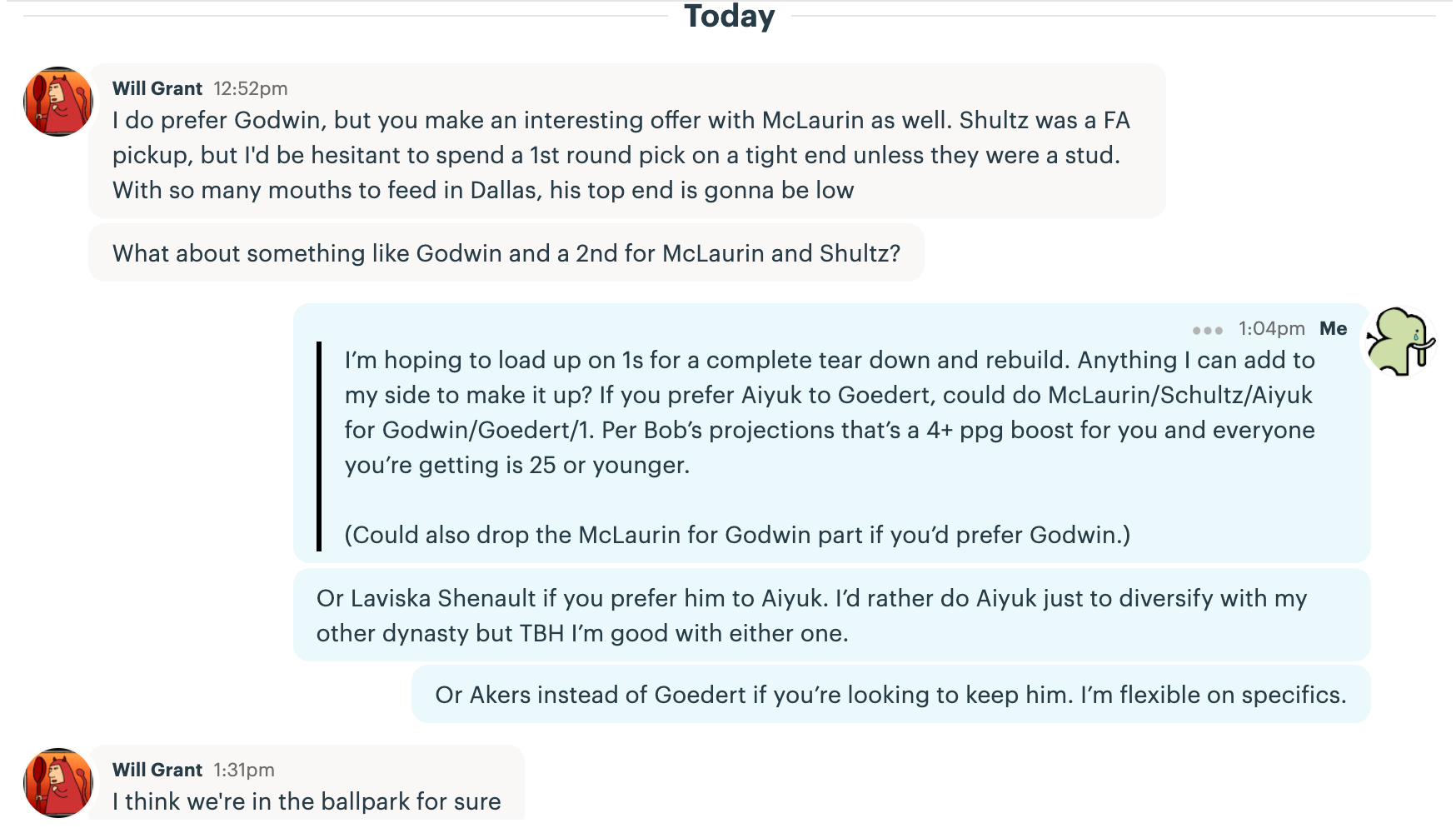

This is where having rough values (and especially of thinking of players in terms of their value in rookie picks), is helpful. I’d consider McLaurin to be roughly equivalent to Godwin. (I prefer McLaurin, the market prefers Godwin, but they’re close enough either way and my desire to diversify is a compelling enough interest for me to be willing to swap for the “lesser” receiver in the deal.)

I’d consider Aiyuk and Shenault to be roughly equivalent to a late 1st round pick. I’d consider Akers and Goedert (with these league settings) to be roughly worth a mid 1st. And obviously I consider his first to be roughly equivalent to a mid-to-late 1st (because he’s 3-1 and according to the League Dominator’s team strength ratings most of the deals I’m proposing will leave him 4th or 5th in projected scoring going forward).

I’m hoping to get a 1st for Schultz. But I’m flexible on how I get that. I can do that deal straight up, or I can deal Schultz for Goedert or Akers, who I consider equivalent in value to a 1st. I can trade McLaurin/Schultz for Godwin/1st. I can add in Shenault or Aiyuk for another piece I consider equivalent in value. Right off the bat I’ve identified dozens of potential trades I’d be happy to make and let Will decide which of those potentials seems like the best value to him.

- Third, notice how I have objective sources to draw on.

“Bob Henry has McLaurin at WR13 going forward but Godwin at WR22”

“Per Bob’s projections that’s a 4+ ppg boost for you and everyone you’re getting is 25 or younger.”

This is a fine line to walk. There is nothing more annoying than another dynasty GM telling you how you should run your team. We’ve all had people come to us with terrible offers and then spend eighteen paragraphs explaining how AKSHUALLY this is a PHENOMINAL offer and THEY CANT BELIEV HOW STUPID THEY ARE FOR EVEN OFFERING IT but we should TAKE ADVANTAGE NOW B4 IT GETS WITHDRAWN.

Don’t be that person. If you want people to trade with you, don’t be someone who is tiresome to trade with. Don’t assume the other owner is stupid. Don’t pretend you’re considering how something impacts their team when it’s blindingly obvious that you’re not.

But *DO* actually consider how something impacts their team. And don’t be afraid to demonstrate that you’ve considered it. It helps to have a few objective sources to rely on. I use Bob Henry’s rest-of-season projections for Footballguys, FBGs’ staff consensus dynasty rankings, DynastyLeagueFootball.com’s staff consensus rankings, and DLF’s dynasty ADP data. The first gives an unbiased take on how deals impact both teams in the short term. The latter three give a rough approximation of general consensus or “market value”.

(If I’m trading with someone who publishes their rankings, I won’t hesitate to use their own rankings as an objective source, too. On the one hand, this can feel underhanded, like I’m taking advantage of a weakness. But really, I think it just makes it easier for me to find situations where both parties like what they’re getting more than they like what they’re giving.)

Again, it’s a fine line. I put the objective information out there and leave it. You don’t want to push it too hard because people will often disagree. (It’s good when people disagree because disagreement is one of the best ways to find value in dynasty.)

But it’s useful to show you’re at least thinking about the trade from both sides and that you’re not trying to pull a fast one over anyone. Again, keeping your values secret is the best path to maximizing possible return. It turns trading into a zero-sum game where both parties are trying to get an edge at the expense of the other.

I prefer to play positive-sum games, to treat trades as a collaborative process, to find deals that leave both GMs happier with the state of their teams. Sure, a lot of the time it’s still going to blow up and leave one person or the other feeling terrible after the fact! But if the process is good they won’t hold it against you if they are the ones who get burned. (Just like you won’t hold it against them if you are.)

Or as the popular saying goes: you can shear a sheep many times, but only slaughter him once.

- Fourth, notice how comfortable I am as the deal grows.

A lot of people are hesitant to make big deals. When I first proposed the skeleton of what would turn into my biggest deal of the year, the other GM responded with

I totally get that. Big deals are scary. There are so many more ways they can possibly go wrong.

But if you have the framework to deal with them, I also think they’re tremendous opportunities for both GMs to win on multiple dimensions. Remember the three reasons to trade? To acquire players you like more, to shift value from the future to the present or vice versa, and to shift value from a position of strength to a position of weakness. Multi-player deals let you accomplish several of these goals at once.

Will wants more points this year. Will is strong at QB and RB but weak at WR and TE. I want fewer points this year and don’t particularly care about the overall composition of my team (other than that a suboptimal composition might actually result in fewer points this year, which would be good for me).

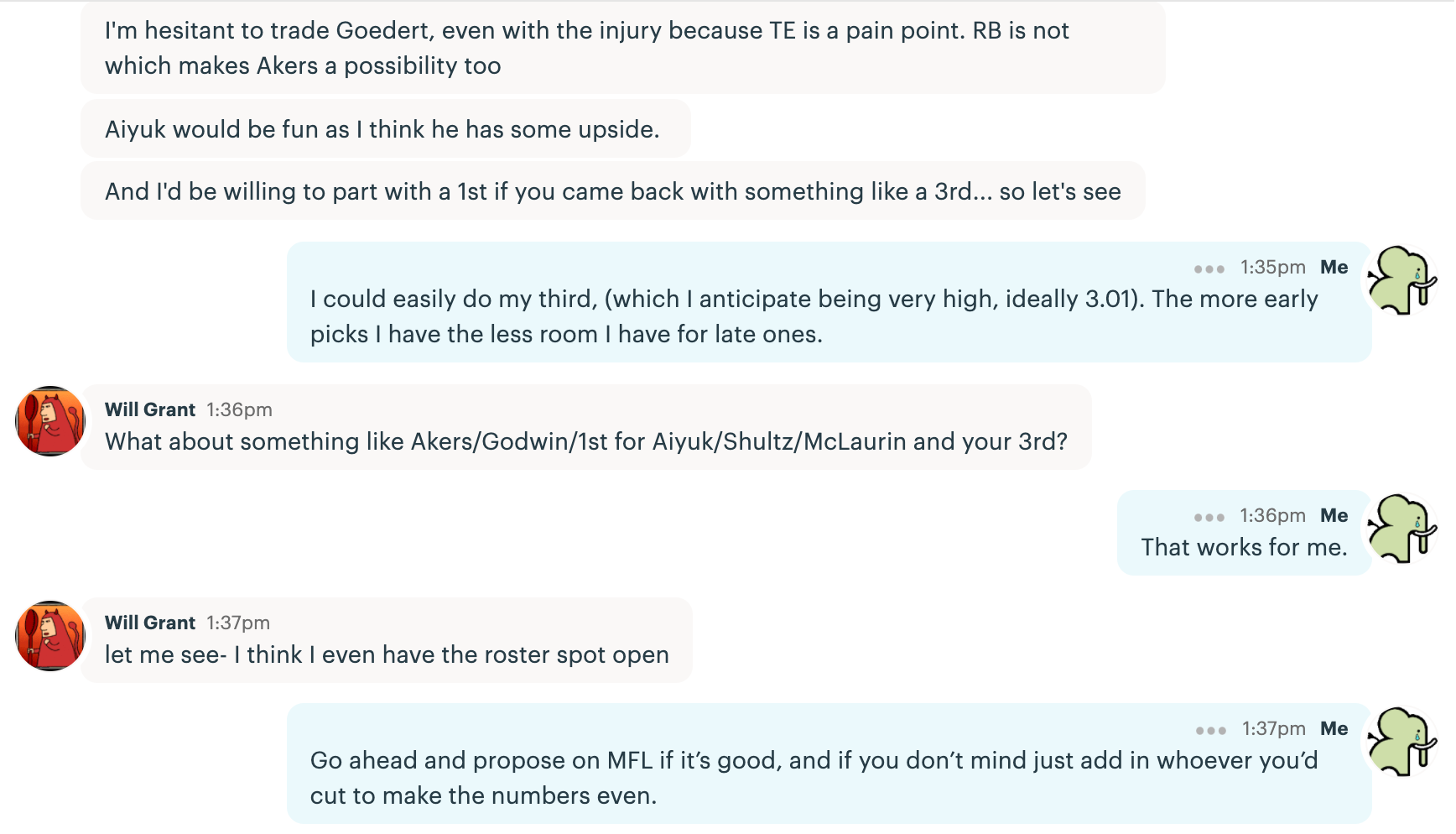

The key is getting that framework to evaluate a larger trade. And the framework I use is to break it down into distinct chunks.

Terry McLaurin and Chris Godwin is essentially a wash for me. (I think McLaurin is better, but Godwin helps me diversify, scores fewer points this year, and would probably fetch a better return on the open market, so I’m indifferent.)

Brandon Aiyuk or Laviska Shenault for Cam Akers is an upgrade for me. In our rookie draft, Akers was pick 7 while Aiyuk and Shenault were picks 14 and 15. Akers has trended down while the receivers have trended up, but I’d still prefer Akers by a little bit. (I’d ordinarily prefer Aiyuk to Shenault, but it’s close enough that my desire to diversify leads me to prefer to keep Shenault if possible. But it’s a weak preference and I’ll deal either.)

Dalton Schultz for a 1st was my desired outcome, while Schultz for a high 2nd was my minimum goal. If I add a third round pick to Schultz– even a very early 3rd round pick– I feel like I wound up in my desired value range. (I just don’t attach much value to rookie picks outside of the top 20 or so, but especially in a year where I’ll already have four picks in the first round; at some point it becomes hard to find room for all the rookies you can draft.)

So that’s three pieces that I think are either a wash or an upgrade for me, which means I’m happy with the larger deal.

But again, there are two people involved in a trade. Why is Will happy with this deal?

Again, comparing Godwin to McLaurin you have two very similar receivers, but in this case Will is getting the guy who is currently productive, helping accomplish his goal of transferring value to the present. Comparing Akers to Aiyuk, Will might be selling low but successfully accomplishes his goal of trading from a position of strength (RB) to shore up a position of weakness (WR). It also improves his present value, because Will is very shallow at WR and Aiyuk will almost certainly be starting for him several times this year. And the 1st for Schultz also transfers future value to the present (while maintaining the potential for long-term value if things break favorably).

This bigger deal satisfies both of our desires much better than any smaller deal would have.

- Fifth, never lose sight of the importance of maintaining relationships.

This deal came together remarkably quickly, but that’s hardly representative. As I mentioned, the vast majority of my entreaties go nowhere. Most of my messages lead to nothing. But they still serve a purpose, because they serve to maintain the reputation I have cultivated and the relationships I have built.

Playing fantasy football is supposed to be fun. I like playing with people I actually like. I trade because I find it enjoyable.

Once Will and I were done talking about the deal, we talked about our fantasy football philosophy. We talked about meeting up sometime once the pandemic was under control. We swapped stories about past coworkers, talked about cars, about fantasy football team names, joked about owning a dog in a big city.

By my count, we sent 29 messages over (mostly) 40 minutes related to the deal, and then once that was done we sent 81 messages over 3 hours and 40 minutes that had nothing to do with the deal.

Why? I could tell you that the small-talk created fantasy value for me. And it absolutely, 100% did: I learned about what some of my other leaguemates were looking to buy and looking to sell and got a hot tip on someone who might be interested in trading for Akers now that I had him. The next time I want to trade with Will is going to go easier because Will knows I don’t just chat with him when I want something from him.

But that’s not why I did it. I did it because I like Will. He’s a friend. The other GMs I tried to trade with are friends, too. The GMs I’ve traded with in the past are friends. Being the type of GM who is friends with his leaguemates undoubtedly makes it easier to complete deals in a “not very active” league, but that’s just a happy byproduct.

I create a dialogue not because I think it’s the best way to make trades happen (though it probably is), but because I like talking with my friends. And if that happens to facilitate trades in the process, so much the better.

Parting Shot #1

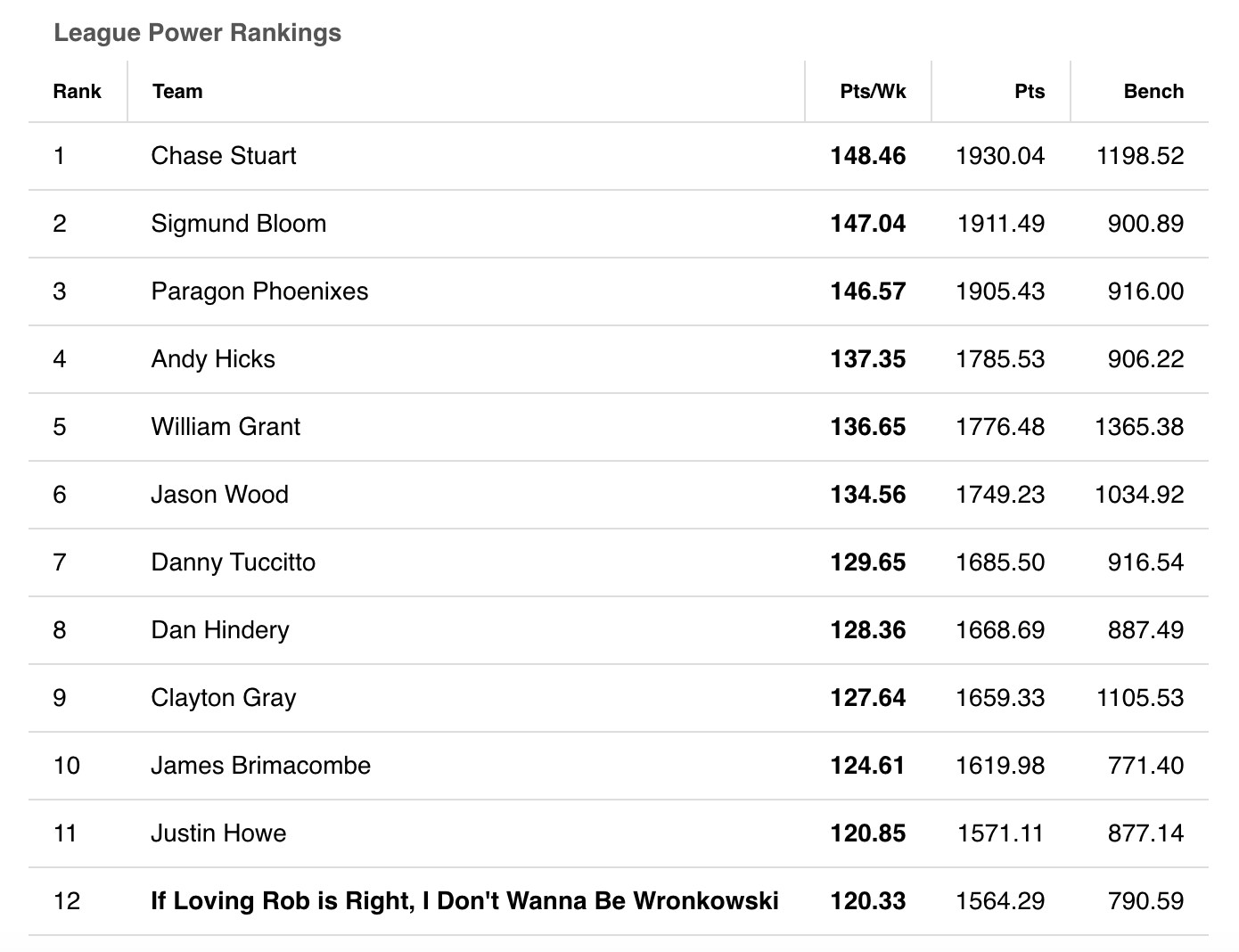

I talked about looking for win-win deals. In part 1 of this series I mentioned making a trade with Chase Stuart. At the time, he and I were projected as the #6 and #7 teams, per Footballguys’ rest-of-year projections. 6th and 7th is the worst place to be– not good enough to win a title, too good to get a high pick, stuck in purgatory between.

So I traded all of my most productive players to Chase for youth and picks. (See above on being comfortable with big deals.) And here’s where things stand today:

Week 5 is not Week 16. But 1st and 12th is a heck of a lot better than 6th and 7th (especially when that 12th-place projection comes with plenty of young talent and three extra first-round picks).

Chase is happy. I am happy. I’m happy that Chase is happy. My reputation as someone who’s not looking to screw the other guy is hopefully burnished in the process.

Parting Shot #2:

Dan Hindery has recently released his

October Value Charts. Hindery is the person whose process most closely resembles my own, which means his rankings and values tend to be quite similar to mine. I do disagree with him some, but I think he’s more highly correlated with me than anyone else in the industry.

So when I’m too busy (read: lazy) to keep my own player values current, I often like to use Hindery’s most recent value charts as a starting point and adjust from there.

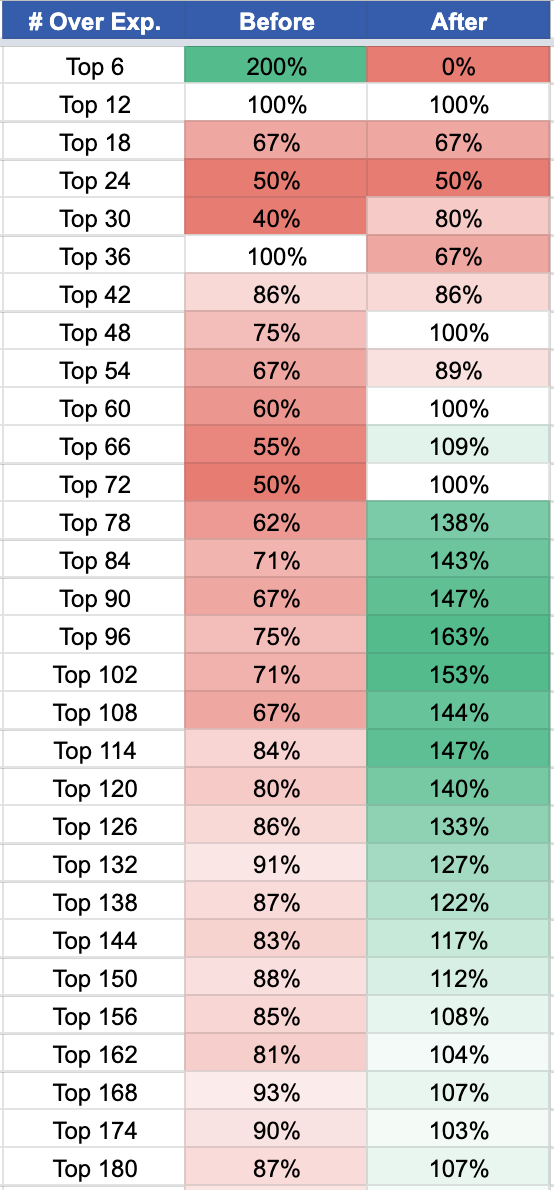

So with that in mind, here’s a visualization of my team before and after the rebuild in terms of overall value per Hindery’s most recent charts. I’ve included estimates of the value of all future picks here, too (including an adjustment for how much higher my own picks are in expectation after the rebuild).

How to read this. In a 12-team league where talent is evenly distributed, each GM should expect to have one Top-12 asset, two Top-24 assets, three Top-36 assets, etc. (Similarly, they should expect to have 0.5 Top-6 assets, 1.5 Top-18 assets, and so on.)

I’ve tallied all my players in each range and charted where I am relative to that expectation.

As you can see, I’ve lost Kamara (Hindery’s new #1 overall dynasty asset), but have gained a massive wealth of assets in the 5th-12th range of dynasty startups.

If value was perfectly evenly distributed among all twelve teams, you’d expect each team to have 287 points. My “before” roster was worth 247 points, or 86% of average. My “after” roster is worth 322 points, or 112% of average. Through alchemy, I’ve essentially increased my team’s value by 1.3x.

The secret? You’ve read the series so far, it’s all about the thesis I posted at the start: success in dynasty is often a matter of just putting in the effort.